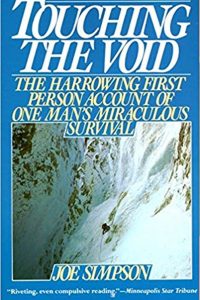

Touching the Void: The Harrowing Story of One Man's Miraculous Survival

I should start by mentioning that I have a strong tendency to be overly cynical when it comes to books about inspirational stories. For one thing, there are too many of them. For another, they tend to be written either by sycophantic onlookers more intent on banging home a message than ferreting out the real facts or by shameless self-promoters with highly inflated views of their own accomplishments.

There are exceptions, of course, and some mighty ones, especially those that are about people who survived unspeakable hardship. Beyond Survival, Gerald Coffee's account of his years as a POW in the "Hanoi Hilton," springs to mind, and there are many books dealing with what it took to survive Nazi persecution during World War II. In both of these examples, the subject matter concerns the brutality foisted upon people by political enemies, and the termination of those ordeals could come about only as the result of a political event, either a negotiated settlement of some sort or a forced surrender. In those cases, the challenge to the victims was to hang on as long as possible, to keep themselves alive until events beyond their control interceded to enable their liberation.

But there's another kind of survival story, that in which passivity means certain death and some affirmative activity is required to save one's own life. And I would be hard-pressed to come up with an ordeal more unbelievable and profoundly moving than the one described in Touching the Void.

Joe Simpson and his climbing buddy, Simon Yates, had gone to South America to attempt the summit of one of the most treacherous peaks in the Andes. Experienced mountaineers, they were well aware that their decision to do this by themselves was a major risk, rescue of an injured climber being a near-impossibility if only one other climber remains healthy. The attempt was made doubly dangerous by virtue of its highly technical nature: this wasn't a simple hike with bad weather and thin air thrown in, but a challenging and complex endeavor demanding highly specialized skills and equipment to negotiate the viciously inhospitable terrain. Simpson and Yates ran into every conceivable obstacle, including precipitously steep walls of ice, yawning crevasses hidden by thin veneers of snow, and blinding white-outs that made it impossible to establish direction beyond a few feet.

Nevertheless, after three exhausting and demanding days, they achieved the summit, pausing only for an hour or so before facing the daunting descent, often considered a more difficult challenge than the climb upward. Somewhere above the 19,000-foot level, as he carefully lowered himself over the edge of a cliff, Simpson slipped and fell, landing on one leg with such force that his tibia was driven upward through his knee. Helpless, freezing and blind with unspeakable pain, he knew that Yates had no choice but to leave him and attempt the fearful descent on his own. It was Yates' only chance to save himself and avoid the needless loss of two lives rather than one.

But Yates, ignoring his mountaineering wisdom in deference to his loyalty to Simpson, elected to chance a daring, one-man rescue of his long-time climbing companion. Tying a rope around Simpson and planting himself firmly in a hand-dug snow seat for purchase, he lowered his badly injured friend down the face of the mountain, tuning out the howls of agony that echoed back up to him as Simpson's shattered leg constantly caught on small obstacles and banged against rocks. When the 300 feet of rope ran out, Simpson, trying to keep himself occupied in a vain attempt to block out the waves of pain emanating from his leg, began digging the next snow seat as Yates climbed down after him. They repeated the process for another 300 feet, and then another, Simpson constantly asking himself whether the next stage of the descent was worth the unbearable torture, Yates ignoring him in his desperation to save his life, even as his own fingers were turning black with frostbite.

This went on until they'd come down 3000 feet. Yates estimated that they might have but one, or at the most, two more stages until they reached a place where walking without ropes would be possible, although neither of them had given much consideration to their means of locomotion once they got there.

Again, Yates lowered his friend down the face, but soon felt a powerful tug on the rope. It was all he could do to hold onto it, but it was futile: Simpson had shot out over a precipice and was hanging free some 30 feet below the rim. Looking down between his feet, unable to see through the storm-driven snow, he had no idea how far below him the ground lay.

There was nothing Yates could do to pull Simpson back up, nor were there any real options after that even if he could. In anguish, he cut the rope and silently bid his old friend farewell as Simpson dropped into space, then he started down the mountain alone and tried not to think about his partner lying dead somewhere above him.

Unbeknownst to Yates, Simpson didn't die. He fell into a deep crevasse and came to rest on a ledge barely wide enough to hold him, hardly daring to breathe for fear of dropping over the side into the inky blackness below. And in case you think I've given the whole story away, let me assure you that it only really starts at this point. Not only did Simpson survive the fall, he got out of the crevasse and, over four pain-wracked days, struggled his way back down the mountain to base camp.

How he did it makes for one of the most incredible first person accounts of survival I've ever come across. In this all-too-short book, Simpson tells of interspersed triumphs followed with depressing regularity by fresh disasters, one after the other. I felt the way I did reading Lost Moon, the book that eventually became the movie Apollo 13: even knowing how it ends (Simpson wrote the book, after all), I literally held my breath, fully expecting him to give up to a quiet death at each setback, astonished instead at the power of his will to live. Even when he finally found himself in a hospital, it still wasn't over: he lay without food, medicine or painkillers for two days until confirmation of his insurance came through.

I can't recommend this book highly enough. You can read it in a day, but Simpson's unflinching description of his experience will haunt you for a long time after that.

- lee gruenfeld