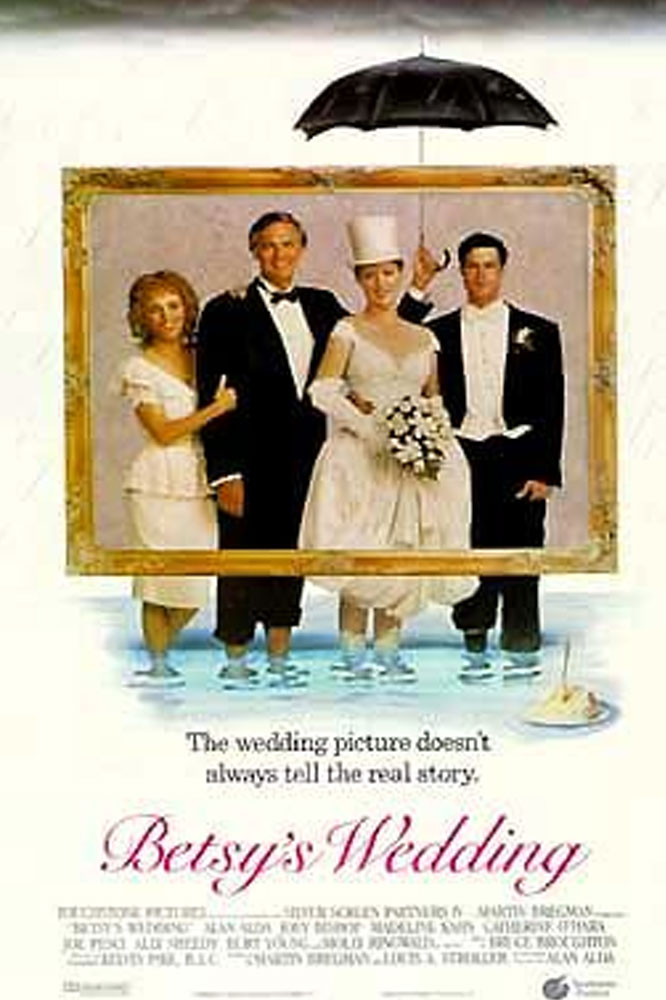

Betsy’s Wedding

An otherwise light and frothy farce, Betsy’s Wedding is elevated by the presence of one Stevie Dee, one of those incredible characters you’ll find yourself imitating, to the great annoyance of your acquaintances, as soon as you leave the theatre and probably for years afterward. As brought to life by Anthony LaPaglia, whom you might recognize as Daniel Benzali’s replacement on the television series Murder One, Stevie Dee (one never calls him just Stevie) is a mob wannabe with a sense of decorum and inter-gender proprietary so over-developed that even the simplest sentences come laden with numerous protestations of respect and restraint. His wooing of the lead character’s sister, played by Ally Sheedy, is howlingly funny as LaPaglia unrelentingly pursues her but spends most of their time together insisting he’s not applying any pressure.

There are wonderful bits contributed by Burt Young as Stevie Dee’s mob uncle, Joe Pesci as a developer so cheap he offers the newlyweds one of his worst slum apartments at a good discount, Madeline Kahn as Betsy’s mother trying to cope with the new, upper crust in-laws, and Sheedy as a female cop. ("I like arresting people," she answers when asked why she wanted to be a cop. "I put ‘em up against the car, kick their legs apart…I’m high for the rest of the day.") Molly Ringwald is perfect as Betsy, a clothes designer with the taste of an 8-year old, especially in a scene where she bargains with the rabbi who is going to perform the ceremony to keep God out of it.

But it’s Stevie Dee’s picture all the way. Hard to describe, really: he has to be seen.

I confess to a strong bias for movies portraying slices of Jewish or Italian middle-class life in New York City, and 29th Street is an over-the-top example of the latter. It’s based on a true story of a cop, Frank Pesce, Jr., who hit it big in the first New York lottery. LaPaglia plays him brilliantly, especially in scenes opposite Danny Aiello as his father with big ideas but small vision. The two go at it as only a pair of Italian males can, with unrestrained gusto, explosive venom and an undercurrent of love that becomes ever more obscured as the events surrounding the lottery itself tentacle their way through their relationship.

The plot is wonderfully clever and revolves around Frank Jr. being the luckiest man alive, the kind of guy who doesn’t even need to watch the finish to know for certain his horse won. Even when he gets stabbed, he’s lucky: a potentially fatal tumor is discovered in the process and removed in time.

The film starts out with Frank walking the streets of New York on a snowy Christmas Eve, cursing the city, his family, his life…even the local church, at which he hurls snowballs until the priest has him arrested. Once inside the station, we discover that this forlorn, misbegotten soul has just won the jackpot in the New York lottery. So what could his problem possibly be? The story develops deliciously in flashback until we discover that there really is a perfectly logical reason why someone would be depressed over hitting it big. Thankfully, a beautiful twist at the end resolves it all, not just the matter of the lottery but Frank’s relationship with his father.