Inspiring Age Groupers: The Legacy of Jon Blais

Looking back on the "Blazeman Warrior" who still inspires pros and amateurs alike.

by Lee Gruenfeld

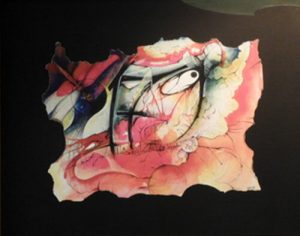

There’s a piece of art hanging on my living room wall. It’s called "179" and there’s a story behind the number partially hidden in plain sight amidst a swirl of color.

Up until the spring of 2005 things were going really well for a guy named Jon Blais. Massachusetts-born, he’d moved to San Diego in order to pursue his passion for triathlon and the multisport lifestyle. A dedicated teacher, he also had a personal mission to work with at-risk, learning-disabled children. He was on the staff of the Aseltine School, which shared his goal of transforming troubled young people into productive citizens.

Up until the spring of 2005 things were going really well for a guy named Jon Blais. Massachusetts-born, he’d moved to San Diego in order to pursue his passion for triathlon and the multisport lifestyle. A dedicated teacher, he also had a personal mission to work with at-risk, learning-disabled children. He was on the staff of the Aseltine School, which shared his goal of transforming troubled young people into productive citizens.

It was all going so well. Right up until May 2, 2005.

A word about amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, better known as ALS: To put it as simply as possible, there’s no positive spin you can put on any of it. it’s a disease in which the nerves controlling voluntary muscles degenerate and eventually die. There’s no heroic fighting, there are no miracles, and there’s no cure. It’s progressive, which means you get steadily worse, and there’s no way to ameliorate the symptoms, which include gradual degradation of your ability to eat, to stand or walk and, eventually, to breathe on your own. It’s insidious and it’s evil, striking otherwise healthy people in the prime of their lives.

Worst of all, your mental functions remain unaffected, which means you are a fully alert witness to your own decline, death generally occurring within three to five years of initial diagnosis. As Jon himself put it, "No one is beating ALS. No one has done anything but walk away and die."

No one, that is, except Jon. He wasn’t a starry-eyed romantic who thought he could beat ALS but he wanted to at least outwit it one last time before it finished him off.

Invited to race in the 2005 IRONMAN World Championship, he harbored no illusions about a great performance – symptoms of his disease had already manifested – and his doctors dismissed the idea out of hand. "The only way you’re going to cross that finish line," they told him, "is if someone rolls you across it."

Fair enough. "Even if I have to be rolled across the finish line," he said, "I'm finishing."

It would be a one-shot, now-or-never attempt. Jon was acutely aware that there wasn’t going to be a second chance.

I didn’t know about any of this at the time, but I clearly remember an odd scene at the finish line. About 31 minutes before the 17-hour cutoff, I saw a guy suddenly stop a few feet before the line, get down on the ground, stretch his arms above his head and roll himself across. He was wearing the number 179 on his race bib.

"It was the longest day of our lives," Jon’s mother Mary Ann remembers. "He carried the weight of so many PALS ('persons with ALS') that day, yet he hadn’t really trained because the doctors thought it would accelerate the progression of his disease."

Chrissie Wellington rolls across the IRONMAN World Championship finish line (Photo: Rich Cruse)

Chrissie Wellington rolls across the IRONMAN World Championship finish line (Photo: Rich Cruse)

Ailing and out of shape, with "Blazeman" shouting from his race jersey in bold letters, Jon dragged himself through sixteen-and-a-half hours of agony so he could stick it to the beast and create one indelible moment of the purest inspiration.

A year later, he was in a wheelchair at the exit of the swim leg in Kona. As athletes came out of the water, many paused and swung over to shake his hand or give him a hug.

Seven months later, the Blazeman Warrior was gone.

That same year, Jon’s parents Bob and Mary Ann formed the Blazeman Foundation, a not-for-profit dedicated to researching cures for ALS. Supporters include such IRONMAN luminaries as Leanda Cave, Andy Potts, Mirinda Carfrae, Matt Reed, and Scott Tinley. They and other triathletes all over the world will often do the "Blazeman Roll" at the end of races, an imitative tribute to the first person with ALS to finish an IRONMAN.

Four-time world champion Chrissie Wellington saw Leanda Cave roll across the Kona finish line in 2007.

"I met Jon’s parents, Bob and Mary Ann, later in the evening of my first world championship," she told me, "and was so moved by his story that I followed Leanda and a few other professionals in becoming a patron of the Blazeman Foundation. We join a team of Blazeman Warriors around the world, committed to promoting awareness of the condition and raising funds for further research."

Wellington has rolled across the finish line of every triathlon she’s done since that day.

Adds Olympian and 2007 IRONMAN 70.3 world champion Andy Potts: "Jon created something bigger than himself when he started the Blazeman Roll. It has continued to bring attention to the cause of ALS and it makes the hardships of racing lighter because you know you are racing for more than yourself."

Blais (center) with Scott Tinley (right), and Rob Vigorito (left), the long time race director of IRONMAN 70.3 Eagleman and a close friend to Blais. Photo taken at the Endurance Sports Awards, courtesy of Bob Babbitt.

Blais (center) with Scott Tinley (right), and Rob Vigorito (left), the long time race director of IRONMAN 70.3 Eagleman and a close friend to Blais. Photo taken at the Endurance Sports Awards, courtesy of Bob Babbitt.

IRONMAN also began a tradition of allowing selected athletes to wear bib number 179 in IRONMAN events. My wife Cherie proudly wore it several times, and the "179" that hangs in our home was a gift from Bob and Mary Ann Blais after she wore it in Kona.

Like I said, there’s no positive spin when it comes to ALS. But there’s a lot we can say about one special man’s extraordinary effort to not cede total defeat. Jon’s race in 2005 wasn’t just a personal victory but a spark that ignited awareness and a more concentrated search for a cure. IRONMAN competitors who knew Jon or knew of him evoke the memory of his superhuman effort to keep themselves going when their bodies threaten to surrender.

The "179" on our wall is a constant reminder that, as Jon showed us, we are often at our very best when things are at their very worst.

Follow our stories of 40 Years of Dreams at ironman.com/40years.