Threshold

Sometimes, perhaps owing to under-powered marketing efforts or Byzantine movie business politics, or just to chicken studio execs, certain films lacking blockbuster stars or other standard pedigrees get undeservedly lost in the noise. These are some examples.

Saving Grace stars Tom Conti as the modern-day Pope Leo XIV who one day finds himself accidentally locked outside the Vatican walls. Intrigued by the possibilities, he wanders around Rome, trying to blend in with the local populace in order to get some feeling for what an ordinary life might be like. Before long, he ends up in a small, nondescript village which just happens to need a new priest, a role he slips into easily. While the pampered, isolated and self-centered Vatican staff (is it possible even to imagine a Curia without Fernando Rey?) drive themselves to distraction trying to cover for the pope’s absence even as they desperately attempt to get him back, the pontiff finds himself absorbed in the lives of his new parishioners and strangely moved by the ordinary travails of ordinary people.

This film studiously avoids grand gesture and cheap sentiment, concentrating instead on the insightful portrayal of how important things can take place in unimportant lives. There are a multitude of charming moments, beautifully underplayed by the talented Conti (Ruben, Ruben) in a marvelously restrained and subtle performance. The occasional cuts between the pope’s highly personal sojourn into the countryside and the consternation among his Vatican handlers that the great man himself would rub shoulders with peasants provides cutting commentary on the arrogant isolation of the church hierarchy from the daily lives of the faithful. That the little village is practically walking distance from the church’s seat of power makes that disconnection all the more poignant.

But don’t get the impression that Saving Grace is a political statement. It’s a sweetly sorrowful and ultimately uplifting labor of love by some caring filmmakers, and whatever commentary it offers is smoothly woven into the story with humor and, well…saving grace.

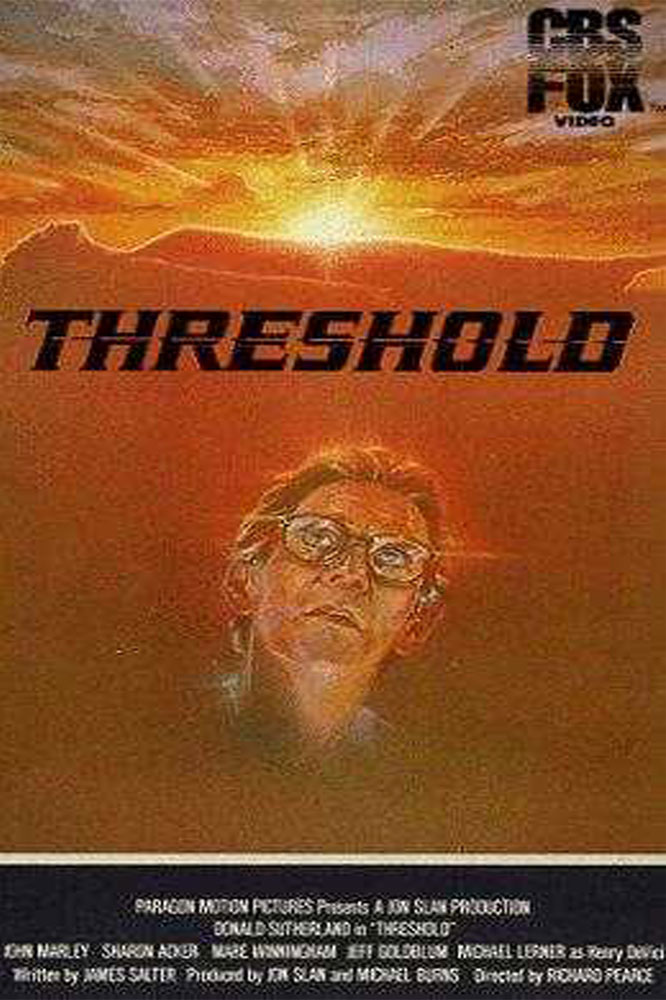

One wonders how Threshold ever got made, since the pitch for it would be difficult to make very exciting, but I suspect Donald Sutherland had something to do with it. He plays a renowned heart surgeon collaborating with Jeff Goldblum’s engineer on a fully self-contained artificial heart. Goldblum’s character is the sole spot of freneticism in this movie in which the rest of the characters act like real people might if they were unaware that a camera was present. There are no histrionics, nobody even raises a voice, to the point where you sometimes have to strain to hear what is being said. So all of the emotion and tension is transmitted strictly by the words they speak and the situations that develop, and this masterful handling of events and human interactions is strangely powerful and affecting.

As if to underscore the non-cinematic reality of what is taking place, there are unexpected turns that no big-budget producer would have allowed. Mare Winningham, in one of her earliest major film roles, is the young girl who receives the artificial heart with no advanced warning. While she is on the operating table (in a scene that uncomfortably demythologizes any illusions we might have held about patient dignity during surgery), Sutherland discovers that her heart is beyond repair. He elects to defy the hospital’s medical board and install the artificial heart. When Winningham awakens out of anesthesia, we expect the typical celebration of successful defiance of moribund authority in the face of radical lifesaving; after all, the new device worked to perfection.

But this film isn’t about satisfying our Hollywood-accustomed desires. Winningham is confused and terrified by the strange device clicking away in her chest, beside herself with anxiety because she’s suddenly unsure if she’s really still human. Sutherland’s surgeon, expecting at least a little gratitude, is totally thrown by this surprising reaction. He’s a mechanic, after all, and he never stopped to consider the human implications on this one particular patient.

The film’s ending is unnervingly beautiful, too. We expect the surgeon to win the Pritzker Prize and be carried through the streets on the shoulders of his colleagues, his entire life transformed into a series of television interviews and lucrative speaking engagements as the credits roll and triumphant music swells.

Instead, he simply starts just another typical day, and we leave him as he routinely plans another round of surgeries and meetings.

There’s no real beginning, middle or end to the events that transpire in the film. Instead, it’s more like we happen upon some interesting people at a point in their lives when something quietly momentous is occurring, hang around for a while, and then leave when it’s basically over. That’s why it must have been a difficult pitch. It’s also why it’s a wonderful picture.

Jackknife is a small film that packs a huge emotional wallop. I’m not going to say much about it beyond urging you to see it, but I will warn you that it’s one of those that marketers and the critics they influence tend to refer to as uplifting and redemptive, but is in fact sad and depressing.

Ed Harris, in one of his best roles, plays a Vietnam veteran so scarred by his wartime experiences that he has shut down like a faulty nuclear power plant, sealing off nearly all the entryways to his emotions and capacity for human contact. He is living with his sister, brilliantly portrayed by Kathy Baker, whom he has pretty much managed to drag down into his personal hell with him.

Robert DeNiro, an army buddy, arrives on the scene as the self-appointed savior on a mission to rescue Harris from his demons. How it happens is so harrowing and powerful it makes you wince to watch it. The emotional pace is relentless, the performances searing, and the only reason the movie wasn’t the big hit it deserved to be was because, well, it isn’t exactly the kind of flick that leaves you humming the love theme on your way out of the theatre.

And, finally, there’s Big Night. There’s an emotional connection here with 29th Street, insofar as it involves a love-hate relationship within an Italian-American family, but there the similarity ends. Where 29th Street is a bravura showpiece of deep feelings exploding unrestrained all over the screen, Big Night is more of an elegant museum piece in which passions are quietly displayed in a more contemplative setting. Also, where 29th Street has a linear plot with a climactic and satisfying resolution, Big Night shares its story concept with Threshold: both are slices of life centering on an important event, at the end of which the characters simply return to normal and the film ends.

Stanley Tucci, who co-directed, and Tony Shalhoub (who single-handedly made Quick Changeunmissable) play Italian immigrant brothers, Secundo and Primo (get it?), who are struggling to make a go of their gourmet restaurant. Secundo is the businessman and schmoozer concerned about pleasing customers and obtaining financing. Primo, on the other hand, is a culinary artist of the first rank, an uncompromising perfectionist who refuses even to prepare a side order of pasta for a customer who is supposed to be eating risotto because her plebeian tastes brand her "a criminal."

Tucci’s Secundo is torn between his respect for his brother’s high standards and the need to make enough money to keep the business afloat. But his exhortations to Primo to accede just slightly to his customer’s desires are snidely rebuffed at every turn, and it’s killing him to watch the wild success of his competitor directly across the street, who fills his eatery to capacity nightly by catering to every garish and tasteless whim.

What action there is focuses on one big night in which Louis Prima himself is expected to visit the restaurant. The brothers put everything they have, financially and emotionally, into preparing the kind of feast not seen since ancient Rome in order to impress the popular singer and perhaps achieve some notoriety for their beleaguered establishment.

Tucci and Shalhoub hit all the right notes in this beautiful film without raising their voices (except in one scene) or making a single superfluous gesture. These two terrific performances are like icebergs, where you only see ten percent directly but the ninety percent below the surface is firmly present and undeniable. There is plenty of humor but it only hides the real desperation, as in a scene where Primo tries to talk a loan officer into some leniency.

And the ending is one of pure theatrical brilliance. Secundo fixes breakfast for Primo, and not one word is spoken. That’s it. Imagine how that pitch would sound to a studio exec, but then watch how it’s pulled off in the movie.