Three Days of the Condor

I put that title in quotes for a reason. After years of enduring the opprobrium of the house critic (my wife) that my novels are too convoluted for the typical book-buyer, that phrase popped up in an important review of my latest, The Expert. Vindication at last? Not hardly. The bride draws a distinction between ordinary book-buyers and professional critics who, as she points out, get their copies free.

Nevertheless, the only guide I have for what to write is what I like to read, which is related to what I like to see in a movie. In plot-driven films what I like is intricacy: puzzle pieces artfully presented so as to increase our confusion while holding out the tantalizing promise of a satisfying conclusion.

Like Forbidden Planet, Three Days of the Condor demands constant vigilance. I first saw this movie with my sister and her husband in a near-empty theatre, so we were free to discuss things as they unfolded without disturbing anybody. It was great fun to speculate about where it was heading and also to remind each other of key plot points as the story developed.

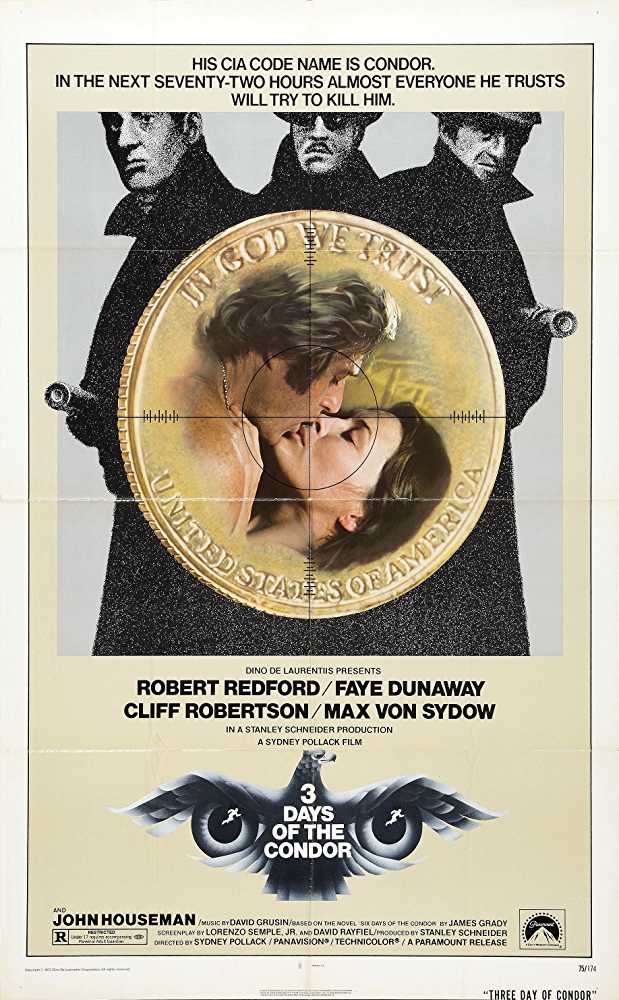

In grand tradition, this movie centers on an ordinary man thrust into an extraordinary situation. In this case it’s Robert Redford, a low-level CIA employee whose job it is to scan books and articles from around the world in the low-percentage hope of spotting something useful to the intelligence community. He returns from a lunch break to find all his colleagues professionally assassinated. Realizing that the perpetrators know they missed one, he is suddenly on the run and takes it upon himself to try to uncover the reason for the brutal hit even as he plays a dangerous and suspenseful cat-and-mouse game with his pursuer, the understated but menacing Max von Sydow. At the same time, Redford has to manage Faye Dunaway, whom he has somewhat inadvertently kidnapped.

The latter situation is strongly reminiscent of that in Starman. In both cases, a woman is held hostage by a man who means her no harm but has no choice. In both cases, the relationship is subtly transformed from one involving fear and hostility into one of trust and empathy, and in both cases the captive eventually sides with her captor and willingly helps him out.

Redford’s character, of course, rises to the occasion. Frankly, it’s a great stretch of credibility how this meek bookworm transmutes into James Bond, but it’s all handled with such skill and style that it isn’t particularly troublesome and hardly noticeable except in retrospect. The ending is very satisfying, too, and calls to mind Absence of Malice in the complete turn of the tables by an initially powerless victim.