Starman & Forbidden Planet

Wait! Come back here!

What is it about science fiction that gives it such a bad rap, to the point that mere mention of that label will prevent otherwise open-minded people from sampling any of it? Is it that the genre has a reputation for forgoing characterization, subtlety and meaning in favor of technical minutiae of dubious merit? Is it that this reputation is largely deserved? What a shame, especially when an occasional effort rises high above the pool of mediocrity and aspires to real art, as do these two wonderful movies.

Forbidden Planet is one of the best sci-fi movies ever (the best being 2001: A Space Odyssey, not reviewed here because it’s hardly a "lesser known"). I’m still haunted by the extraordinary premise, which unfolds slowly, eerily, until the awe-inspiring truth is at last revealed.

A spaceship captain (Leslie Nielsen) and his crew travel to a planet where, years before, another ship crashed, leaving only passenger Dr. Morbius (Walter Pidgeon) and his daughter (Ann Francis) alive. In the intervening years, Morbius has made a life for himself and his daughter, utilizing machinery left behind by the vanished native race of the planet, the Krell. Theirs was a culture so advanced that they had essentially transformed the entire planet into one great, self-sustaining machine, designed to do their bidding and free them from the constraints of their physical bodies.

But somehow, on the very eve of the initiation of this epic phase of their culture, the entire race disappeared, in a single night. Despite his mastery of the machines they left behind and the knowledge of Krell history he acquired from them, the reason for this catastrophe remains a complete mystery to Morbius.

Meanwhile, mysteries abound even in the present. As Morbius becomes increasingly agitated by what he perceives to be the disruptive presence of the visitors from Earth, an unseen force is stalking the visiting spaceship, terrorizing the crewmembers and killing them off one by one.

How these seemingly disparate elements eventually collide provides a stunner of a revelation that explains everything, one of those take-your-breath-away twists that makes you re-think everything you’ve seen since the film began. In fact, Forbidden Planet is even better the second time around, because then you realize the relevance of all the details that seemed incidental at first, from the Krell "image machine" that almost killed Morbius the first time he tried to use it, to a heretofore tame pet tiger that inexplicably threatens the visiting crew.

I saw this film for the first time when I was very young; later in life, after formally studying psychology for several years, I went back and saw it again, and only then did I understand the full set of Freudian implications represented. This intellectual tour de force is definitely wasted on young kids who just won’t get it.

The special effects are beautiful rather than technically impressive, incorporating a lot of deep Technicolor reds and blues that enhance the overall tone of otherworldly strangeness that is at once frightening and compelling. The film is also notable for the debut of Robby the Robot, who provides most of the film’s comic relief, and an eerie score by Bebe and Louis Barron.

Where Forbidden Planet finds its center in the brain, Starman is strictly from the heart. It is a profoundly sad movie, unoriginal in conception but striking in execution, containing no new revelations or insights but presenting old ones with special conviction and power.

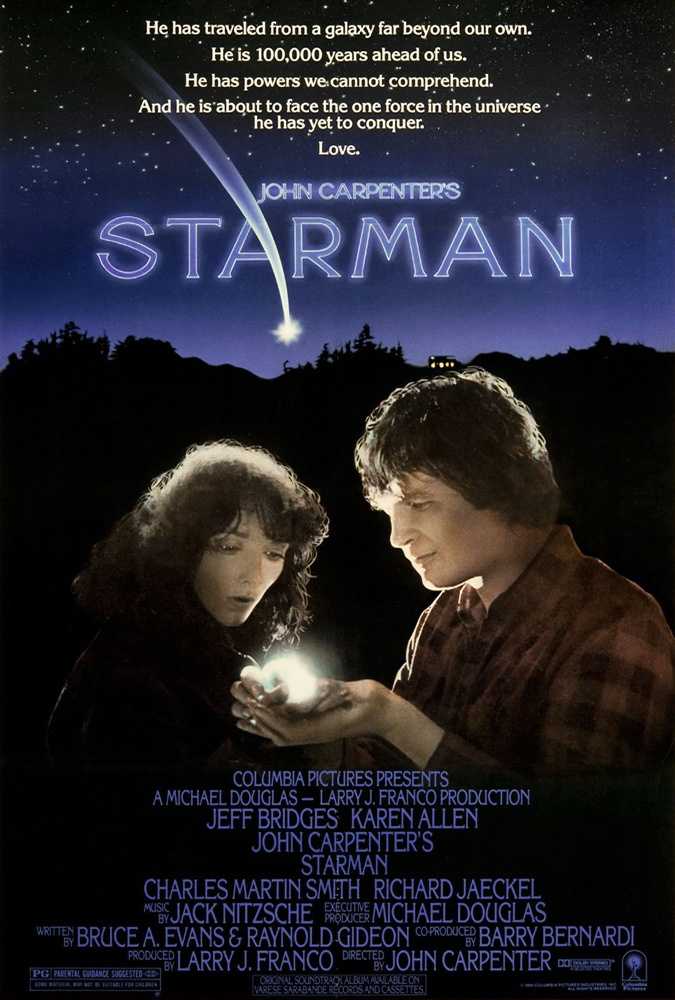

Jeff Bridges, one of the best actors working today (and who gives what might very well be the least-seen Academy Award-nominated performance since Judy Densch's for Mrs. Brown), is a non-corporeal visitor from an unnamed planet who lands on Earth and ends up in the house of recently-widowed Jenny Hayden (Karen Allen). Utilizing various visual memorabilia in the house (photos, old home movies), the visitor assumes the dead husband’s physical form, much to the shock of the widow, whom he then kidnaps and takes on a road trip. Predictably, most of the movie involves their growing relationship in the forced confines of Jenny’s captivity.

But what really sets this movie apart is Bridges’ performance, one of those deeply satisfying achievements in which an actor manufactures a complete persona from scratch while we watch. The premise here is that this alien visitor arrived as a total blank, the prefect tabula rasa upon which a new character is writ, and he does so using nothing other than what he sees around him. Thus, in his first attempt at driving, he careens through an intersection against the light because he based his learning on Jenny’s behavior or, as he explains it: "Green light – go. Yellow light – speed up." He seems to have a purpose, although what that might be we can’t tell, but his modus operandus of fashioning himself solely from his observations is apparently based on the supposition that human behavior is consistent and predictable. The fallacy of this assumption gets him into constant trouble, and we can’t help but wince at such pure innocence rewarded with pain and confusion.

Which brings us to the heart of this character: We might be forgiven for believing that the visitor will eventually be cast in the same cynical mold as his models. After all, what else has he to go on? Incredibly, though, his own "personality" shines through, and Bridges imbues that personality with a mix of dumb naivete and penetrating wisdom that is a wonder to behold. As he develops, and as his gentle and forgiving nature becomes apparent to Jenny, she abandons herself to this image of her lost husband, only to discover that prolonging his stay on Earth will mean the visitor’s death. Despite an intended uplifting ending (the inevitable and hopelessly cliched government pursuers are outsmarted by one conscience-stricken scientist, well-played by Charles Martin Smith), nothing can relieve our despair that the pain-wracked Jenny, already tortured by the untimely death of her beloved husband, loses him for a second time.

Interestingly, while the film screams "sequel" (the visitor impregnates Jenny before he leaves), there never was one, perhaps because there was insufficient action at the box office to warrant green-lighting a second movie. A lot of people missed out on a beautiful movie…all because of a label.

I’m not sure that The Dead Zone qualifies as science-fiction. It’s centered around a character with ESP but that’s as far as it goes. The reason for its lack of box office success is related to that of The Nightmare Before Christmas, its purported pedigree: how many people over the age of thirteen are interested in seeing a film based on a Stephen King novel with the word dead in the title? So once again, the kids didn’t like it and adults wouldn’t give it a try.

Again, too bad. This is a little beauty of a film with a great plot, appealing characters and a moody tone and look that are completely absorbing. Christopher Walken plays a young man who awakens from an accident-induced coma to discover that he can sense things by touching people and objects. He retreats from the problems this causes him (in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is an outcast) but keeps getting pulled back into the very kinds of situations he wishes to shun. It seems that every good turn he attempts to do for worthy and sympathetic individuals somehow backfires on him. I won't go further into the plot because there's no way to do so without ruining all the surprises, but it's clever and involving and one hundred percent character-driven. Walken -- who, let's face it, is a very talented weirdo -- has never been better (except perhaps in Pennies from Heaven).