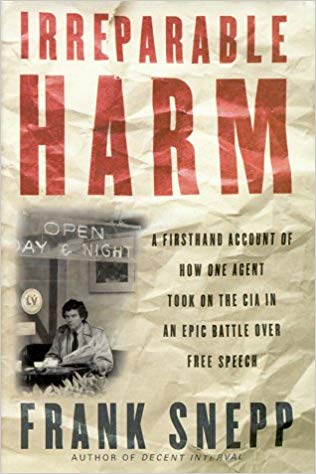

Irreparable Harm*

A Firsthand Account of How One Agent Took on the CIA in an Epic Battle over Secrecy and Free Speech, by Frank Snepp (Random House)

[* Not to be confused with Irreparable Harm by Lee Gruenfeld, a different book]

Were it not for Frank Snepp, the world might never have learned the true story behind America's cowardly, inept and utterly reprehensible abandonment of thousands of doomed South Vietnamese who had been loyal to the U.S. for years and who had been led to believe that they would be protected at the war's end. That Snepp himself was complicit in both instilling that trust and abrogating it later in no way diminishes the impact of his exposure of the shameful fall of Saigon.

As an officer in the Saigon branch of the Central Intelligence Agency, Snepp was the darling of both the station chief and the U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam. He steadily advanced his career and his stature by eagerly participating in the creation and dissemination of intelligence analyses that formed the core of a body of self-deception that, for politically expedient creativity, rivaled the kinds of propaganda for which we ridiculed the enemy. He finally began to snap out of it only in the very last hours of the U.S. pullout, in much the same way as a sinner on his deathbed attempts with his last gasps to atone for a lifetime of transgressions.

But his eleventh hour pleas for the rescue of thousands of South Vietnamese who had diligently served U.S. interests during the war went unheeded. As Snepp's own helicopter, the very last to leave, ascended safely away from the upturned faces of the wretched multitudes watching their only hope of salvation shrink to a pinpoint in the sky, his thoughts were on one face in particular, that of his sometimes mistress who, only hours before, had killed both herself and the baby she'd claimed was his rather than fall into the hands of the conquering North Vietnamese as a result of Snepp's failure to effect her rescue. The horror of that episode set the stage for his subsequent effort to make amends.

Snepp wrote a shocking and historically vital book called Decent Interval which, despite its cathartic genesis, was a meticulously researched and soberly written account that placed the fall of Saigon squarely on the (blessedly abbreviated) list of acts of shame in U.S. history. In performing the redemptive act of writing and publishing Decent Interval, Snepp knew he was tickling the dragon's tail and braced for the onslaught, but nothing could have prepared him fully for the wall of fury that came crashing down on him. The CIA, not at all amused by Snepp's portrayal of its role in the sordid abandonment, charged him with violating his security oath by not submitting the manuscript to agency censors prior to publication. The case was fought all the way to the Supreme Court.

From his perspective, the critical issue boiled down to whether the CIA should be allowed to hide beneath the umbrella of national security to protect itself from allegations that, while certainly terribly embarrassing to the agency, in fact had no real security implications at all. While that issue is probably a bit grayer and more ambiguous than Snepp would have us believe, it in no way renders moot the critical importance of Irreparable Harm, the book in which he skillfully presents his side of that debate by recounting the odyssey of his battle with his former employer.

Which doesn't mean you should read this book strictly as a scholarly polemic. Irreparable Harm is rendered in intensely personal and often achingly honest terms, and is remarkably literate and swiftly paced. While it is true that some stricter editing might have protected us from occasional lapses into overwrought prose, many of these are (almost) forgivable when one realizes that the author is simply struggling with the inadequacies of language to convey the true depth of his outrage and frustration. Overall, the quality of the writing is splendid, at times breathtakingly so, and the book is as compulsively readable as the very best of thriller fiction.

One of the elements that makes the book so powerful, aside from the inherent drama and importance of the story, is the author's brutal candor about his own failings. There is no pretense here of preaching from a pulpit of ethical purity; Snepp does not shrink from accepting liability for some of the situations he decries, although he does adopt a very high tone of born-again moral superiority once we get past the evacuation itself. Snepp takes self-flagellating pains to continually own up to his significant character flaws, as if doing so will, by contrast, convince us of the credibility of his central thesis, which rings true as the facet he cares most deeply about. As a literary conceit, it works, and erases suspicion regarding his motivations. Thereafter, the power of his message is only enhanced when we learn of the enormous personal cost attendant to the publication of Decent Interval: not only was he stripped of his profits from sale of the book, he was placed under a lifetime court order so severe it essentially forbids him from writing so much as a laundry list without first submitting it to the CIA for approval.

The battle between the public's right to know and the government's legitimate need for secrecy in many of its activities is one that will rage as long as democracy exists. Indeed, we're only in real trouble if that debate is silenced. It would be interesting and valuable to have someone as articulate as Snepp write this story from the government's point of view because, filtered through this author's eyes, our picture of the opposition is hopelessly skewed. Few, if any, of Snepp's adversaries are painted in anything but stereotypically villainous colors. There are lacquered blondes, fleshy-faced men, women in ratty Gucci's with "severe page-boy" haircuts and chipmunk faces...the opposition never merely speaks, but howls, rants, whines and chokes up tearfully. One paragraph in particular (page 305) is so gratuitously vengeful it threatens the already tenuous foundation of reasoned discourse to which the book aspires. As it is, some of his legal rationales sound terribly strained: an erroneous representation made to him that the oath he signed as he left the agency was the same as the one he signed when he entered is presented as a rationale for ignoring that first one altogether. Another legal argument exculpating breach of his oath is that the Agency broke its contract with him by denying his legitimate request for an after-action review of the Saigon situation, and therefore this absolved him of any and all unrelated obligations. To a lay reader, these appear to be the same kind of highly suspect interpretive stretches for which he constantly castigates his persecutors.

And while Snepp's contention that even to this very day he's never revealed a single bit of classified information is well-supported and believable, it begs the question of whether he, or any other mid-level Agency staffer, is qualified to make that determination on his own. This conundrum, which was repeatedly brought up by CIA personnel and their attorneys and lends logical, if not moral, credence to the proponents of pre-publication review, is the one sticking point in the author's overall presentation that is never adequately dealt with.

Finally, there is the stinging bottom line, which is that the author lost his case at the Supreme Court level.

But even though that final insult to an incredible personal and legal odyssey would seem to give us as readers great pause, it can also be seen to bolster the credibility of the author's point of view because certain troubling issues refuse to go away. For one thing, Decent Interval revealed no secrets covered by the security oaths Snepp signed. The CIA never claimed it did, only that he didn't submit his manuscript for pre-publication scrutiny and approval. Despite that, the presiding judge in the trial, presented here as having decided the case even before it started, in his written opinion essentially found Snepp liable for something the government never even claimed he did. The Supreme Court itself appears to have made serious errors as well: Snepp learned years later that the only reason his application for review was even accepted in the first place was because Lewis Powell wanted to harshly punish him for what the eminent jurist assumed he'd been charged with, which was dead wrong. Astonishingly, following a speech after the case had already been concluded, someone in the audience pointed out to Powell that he seemed to have gotten Snepp confused with another ex-officer, one who had revealed secrets. One is left to wonder whether the same confusion reigned in the decision Powell dragged his brethren into supporting, a summary judgment that was handed down without Snepp's attorneys even having been afforded the opportunity to argue the case.

Of importance to us as citizens is the agency's true motivation in hounding Snepp so mercilessly on a niggling technicality. Why did it so furiously drive toward a conclusion that accomplished nothing of substance other than perhaps to transmit a warning to future employees who might face similar temptations to violate the sacred rules of the old boys' club of the U.S. intelligence community?

According to Snepp, the answer lies in the fact that the Agency never went after William Colby for the exact same offense, that of failure to submit a manuscript for pre-publication censorship when he published his memoirs, nor did it pursue Graham Martin, the ambassador to Vietnam who presided over the fall and who spirited away a trunkful of classified intelligence documents that were discovered only after he'd left them in a car that was stolen. Quite simply, Colby and Martin wrote sympathetically of the Agency and slinked away unscathed, while Snepp, fiercely critical, was...irreparably harmed. Such selective prosecution, not in the service of national security but to persecute those with the temerity to embarrass the CIA, is the source of Snepp's outrage in this book, just as the horror of the last days of the war had been in Decent Interval. Adding to his profound frustration was the fact that the CIA failed to disclose the Colby and Martin incidents during the trial; by the time Snepp find out about them (from a journalist in France, who told him that Colby had screwed up so badly that the French edition of the former director's book had been printed with classified information that had been deleted from the U.S. version), the appeal was already underway and new evidence was inadmissible.

There might have been a secondary precipitating factor in the Agency's puzzling zeal, though. As I said, Snepp is nothing if not honest, and takes great pains to make sure we understand that he was fairly consistent in his interpersonal dealings, which were self-centered, arrogant, frequently dishonest and almost always grating. One wonders if some of that rankling behavior didn't make it easier for the Agency to zero in on Snepp as a test case for its censorship practices. It might have been harder for the government attorneys to be so relentlessly destructive had Snepp given them more reason to be sympathetic to him as a human being. (Had they known how they would be treated in Irreparable Harm, they likely would have been even more vicious.) Indeed, inconsistent testimony tantamount to outright lying by the likes of Stansfield Turner and others seems to have been borne at least partially from a desire to hurt Snepp as much as possible.

As I said, the free speech vs. national security debate is one that should go on forever, and it likely will, if future participants in the controversy produce works even half as compelling and frightening as Irreparable Harm. If you're not already properly skeptical and cynical about what you hear emerging from the mouths of government officials, you owe it to yourself to read it, especially the final sections that lay out the broader implications of U.S. v Snepp. If that doesn't ruin your sleep, nothing will.

Incidentally, the full text of the book was vetted by the CIA prior to publication

-Lee Gruenfeld